Hotel Lobby

Edward Hopper has been one of my favourite artists since I started taking an interest in art. Along the wall leading to the cafeteria at school, we had a frieze of Seurat’s pointillist painting, ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Queuing for lunch I lazily examined it and, knowing nothing of pointillism, even the term, I was intrigued. Was it allowed, painting in this manner? Dots?

I don’t suppose Edward Hopper was so surprised when he came across Seurat; as an artist he would know there were no rules, only one’s own interpretation. He once said, “My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate expressions of nature.”

He has also been quoted as saying that he always thought of himself as an Impressionist and admitted to being influenced by some, using a lighter palette and freer brush strokes whilst in Paris, where he met with Albert Marquet. Was he fleetingly influenced by the Fauvist movement? Looking at ‘Gas’, painted in 1940 with its bright gas pumps and dark green woods bordered with orange grasses one can almost think so). At the same time he encountered Sickert, a post impressionist, and Felix Vallatton, whose indoor scenes may well have influenced Hopper’s work. He admired Courbet’s style; though in later years confessed to thinking Cezannne’s work was ‘rather thin’.

Hopper was a young and impressionable twenty-four year old when he first went to Paris after completing his training, not to study but to paint and observe. Looking at ‘Gloucester Beach Bass Rocks, a watercolour painted in 1924, there is a hint of Impressionism. Scratchy definition, the hints of shade and the languid poses give us a sense of the heat of the day. The backs of a faltering row of people sitting on the beach, some holding gaily coloured umbrellas, two on deckchairs, and a solitary figure at one end are seen on almost white sand, the collar of sea beyond is a deep blue, and the big open sky ranges from near white to summer blue. Beyond the lone figure the tip of another umbrella peaks into the picture, hinting at things going on just beyond our sight.

Interestingly, in 1913 his first sale was at the Amory Show, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, in which the 1300 pieces included work by Van Gogh, Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Degas and Seurat. The painting was entitled ‘Sailing’, a dark green sea, a lemony sail; the boat reflecting both colours scurries across the surface of the ocean, two indistinct figures at the helm. Perhaps looking at this painting, though, he is more Post Impressionist, as we have come to consider Van Gogh, and as his art progresses he seems to swerve into American Realism. But, ultimately, he developed his own unmistakable style, just as a musician can be recognized by his style of playing.

At his parents’ behest he began training as an illustrator, in order to secure a living, but quickly incorporated painting into his courses. He always saw illustrating as a way of paying the bills and as soon as his paintings began to sell he abandoned it, but at the time, illustrating taught him to watch people, for his editors wanted people, people depicted in a myriad of situations.

After Paris came trips to London, Amsterdam, Brussels and Berlin, always seeking out the art the cities had to offer. In Amsterdam he saw Rembrandt’s ‘Night Watch’ and declared that it was the most wonderful thing of his he had ever seen. Back in New York he took another job as an illustrator with an advertising agency. His recognition at this time was as such; winning first prize in a war poster competition. He also became a self taught etcher and between 1915 and 1924 created around 70 etchings, garnering much praise from the New York Times, and The Evening Sun, which wrote that ‘Edward Hopper’s sincerity carries well in black and white.’ Two good examples of his etchings are ‘Night on the El Train’ (1918) and ‘Night in the Park’ (1921).

In 1923 he met Jo Nivison. Nivison also painted, though her day job was teaching. It was she who brought Hopper to the attention of the curator and director of the Brooklyn Museum; they had invited Nivison to show 6 of her watercolours in an exhibition of drawings and watercolours by American and European artists. Hopper was known to them as an etcher but not as a watercolourist.

Hopper attracted great praise from the critics, most of whom ignored Nivison, (though she was in good company, among others; Georgia O’Keefe and John Singer Sargent were dismissed as ‘other Americans’), and it clearly did not affect their relationship, as a year later they were married. The museum bought ‘The Mansard Roof’ a picture Hopper later described as one of his good early watercolours, for $100; it was his second sale. Later that year he had his first one man exhibition, 11 watercolours, all sold, $100 dollars each. He was 42 and was finally able to give up commercial art and follow his heart.

Hopper’s success in the art world waxed, his wife’s waned, she continued to paint, sometimes the same subjects as her husband, but mostly she deferred to him and dealt with his correspondence, keeping the records of his work and exhibitions. He did not encourage her in her art, ‘a pleasant little talent’ was how he referred to it. Perhaps he could have phrased it a little better, though he was the better artist, after all, she was not unknown in the art world in New York. He clearly didn’t undermine her greatly, she became the model for most of the figures; he admitted to feeling uncomfortable with models and had often worked from photographs. The couple gave the impression of being perfectly self contained.

Edward Hopper’s paintings are eclectic, he had a different way of looking at even the most ordinary of subjects; he said he hoped there was something in his paintings which words could not convey.

Rural America, gentle bucolic scenes of dwellings in harmony with the land, lone figures looking into the middle distance, a scantily dressed lady in her doorway, surrounded by endless space. They have integrated themselves in the romantic view Americans have of their own, far more bloody history.

‘Railroad Train’ from 1908, catches the last carriage and a half as the train steams off. Typically, Hopper leaves us to imagine the rest.

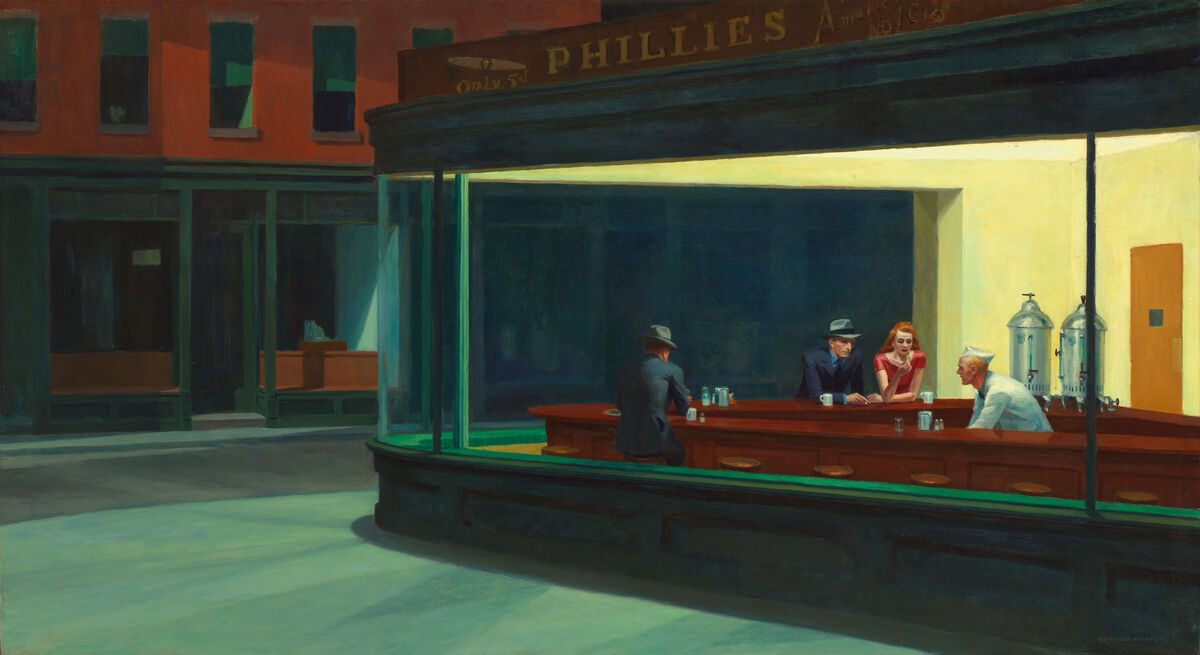

‘House by the Railroad’, painted in 1925, is a tall gothic house with a railway line running directly in front of it, obscuring the very bottom of the building. Alfred Hitchcock was inspired by this painting when creating the Bates’ house in Psycho. Hopper’s work caught the imagination of directors. Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner was influenced by one of Hopper’s most famous paintings, ‘Nighthawks’, in which three seemingly disconsolate people can be seen through the wide glass window leaning at a bar; outside is the night. Wim Wender, a German director admitted to paying homage to Hopper in his films, ‘The American Friend’ and ‘Paris Texas’, the latter being particularly full of ‘Hopperesque scenes.

Urban America is portrayed in hotel rooms and cafes, roof tops, tenement buildings and lonely travellers on trains. Some of his domestic scenes, for example ‘Hotel by a Railroad’ in which a man stands smoking looking out of a window whilst his half dressed woman seems to be reading, are so intimate it is almost voyeuristic to stand looking.

‘Eleven A.M.’ depicts a girl, naked apart from her shoes, sitting looking forward out of the window of an apartment. Her face is hidden from view by her lustrous hair; a table lamp with a large red shade dominates the corner of the picture.

‘Two on the Aisle’ is set in a theatre, before the show, as the first few people arrive. The Hoppers enjoyed both the cinema and the theatre; Jo had trained as an actor. As an aside, it is interesting to note that Hopper was less impressed by Jean Cocteau’s ‘Orpheus’ instead much preferred films by Carol Reed, ‘The Third Man’ with Orson ,Welles and ‘The Fallen Idol’ with Ralph Richardson. He was clearly not taken with fantasy.

Between 1943 and 1955 Edward Hopper and Jo made several trips to Mexico. though he was not always happy there, complaining about the food, the heat, the rain, and on their first visit the lack of a car, he did manage, with his wife’s encouragement to paint, producing scenes of Mexico which conveyed the arid heat and strong light of the country.

‘El Pacio’ is a watercolour from 1946, a view of the top halves of a streets’ flat roofed buildings, one of them the movie house, Palacio. The streaky sky has a look of dawn or dusk, quiet and serene.

Hopper’s oil paintings are usually in sharp focus, light and shade play big parts in many scenes, sunlight streaming through windows, an odd lighted window in a row of apartments.

His seascapes are sunny and colourful, lighthouses and seaside houses set against feathery blue skies, sailing boats with full sails riding the waves. Hopper’s hometown was a seaport and he loved sailing; he and Jo regularly sailed on Cape Cod.

‘The Lee Shore’ from 1941 is full of movement. The boats’ sails are full; one small boat leaning at a daring angle and the clouds seem to race across the sky.

Edward Hopper was a quiet man, not given to self aggrandizing, though he was awarded many gold medals and won prizes for his art. Not, it seems the easiest man to live with, from some of his wife’s diary entries, but they were together for over forty years and his last painting ‘Comedians’ is of himself and his wife, on a dark stage, both dressed Pierrot fashion, taking a bow. The couple had spent most of their lives in a top floor apartment with few amenities, (74 steps up to their apartment) though they did build a house in South Truro, Massachusetts, where they spent most summer months.

When he died in 1967 at the age of almost 85, all his work, over 3000 paintings, drawings and prints were left to his wife, and on her death all of it went to the Whitney Museum of American Art. (see the reprint of Jane Allen Adams’ and Derek Guthrie’s Chicago Tribune review of the first exhibition of this bequest in Milwaukee (next page.)

Lynda Green

Volume 34 no.2 November/December 2019 pp 7-9